A recent conversation with friend reminded me how little most people know about gardening with native plants—information I sometimes take for granted because I’m so interested in the subject. I assume everyone is as interested, but the reality is that more could be. I’m going to take this opportunity to recap some of what I’ve learned and synthesize information from many sources. If you’re new to native plant gardening or curious about it, this post is for you.

What is a native plant?

When my friend asked this, I could barely contain my glee. At last, a willing audience! A native plant is one that was growing in this area before it was developed, so when Lewis and Clark passed by in 1804, they might have seen it. Back then, this was prairie. Few trees grew to significant size because the area was regularly raked by fire. In fact, mature trees were so noteworthy, they became landmarks and place names, like Lone Elm and Cottonwood Falls. The prairie stretched from the Gulf of Mexico up to Canada, and provided habitat for millions of different creatures.

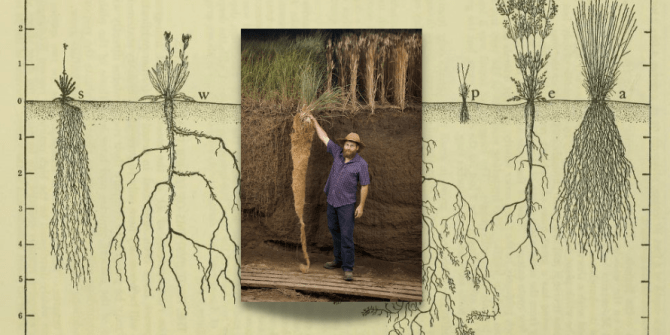

The prairie was predominately grass. In Little House on the Prairie, Laura Ingalls Wilder describes the grass stretching all the way to the horizon like the sea, and growing so tall that a man could ride through it on horseback and she couldn’t see the top of his hat. The grass was perennial—it came back every year without having to be reseeded—and its roots plunged deep into the earth, sometimes as much as ten feet. They helped filter groundwater, mitigate flooding, and hold the topsoil in place. (Many local governments have recognized the advantages of these deep-rooted plants and encourage homeowners to plant them through programs like Johnson County’s Contain the Rain.)

When settlers plowed up the native grasses, they created the Dust Bowl. In The Worst Hard Time, author Timothy Egan explains that the 1920s were a wet decade. Farmers were encouraged to put as much land as they could into cultivation. However, the thirties were dry. The Dust Bowl was an unintended consequence of human actions.

In addition to grasses, prairies were also home to a profusion of wildflowers—like coneflowers, asters, black-eyed susans, and pflox. Many early settlers remarked upon the flowers in their journals and letters home, helping create the impression, as writer Rinker Buck notes, that the American Plains were a land of abundance, and worth settling.

So, why are Native Plants important again?

There’s another piece to this story, having to do with insects. Many people know about the link between monarch butterflies and milkweed. A butterfly starts as an egg, grows into a caterpillar, becomes a chrysalis, and then emerges as a beautiful winged creature. Monarchs have evolved alongside one particular kind of plant, Asclepias, or milkweed, the only kind their caterpillars can eat. If we don’t have milkweed, we won’t have monarchs.

What many people don’t realize, and what I didn’t realize, is that thousands of native insects have a relationship like this with certain native plants. They’re known as specialist insects, and the plants are called hosts.

By the time an insect reaches maturity, it’s a generalist. It can feed on many kinds of nectar-rich flowers—they don’t have to be native. But without host plants, specialist insects cannot reproduce or survive.

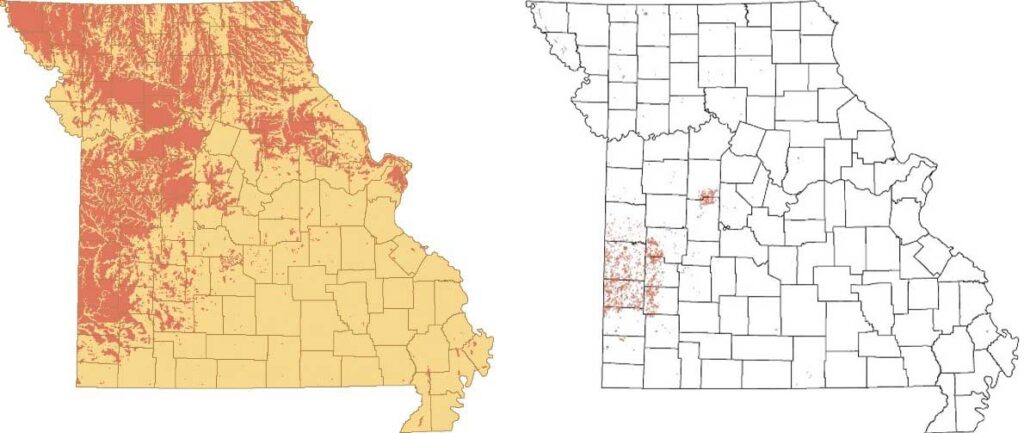

You may have heard that insects—like bees, butterflies, moths, and beetles—are in decline. Many folks my age remember summer road trips that left our windshields spattered with bug bodies. Not anymore. Researchers estimate that insect populations have decreased by 45% in the past forty years. Causes include loss of habitat and pesticide use. Habitat loss is easy to see. The prairies and prairie plants that once stretched across the continent are gone. The land has been plowed up and developed. This image, which I borrowed from the MCPL website, shows how much of pre-settlement Missouri was prairie before Missouri became a state, and how much prairie remains today.

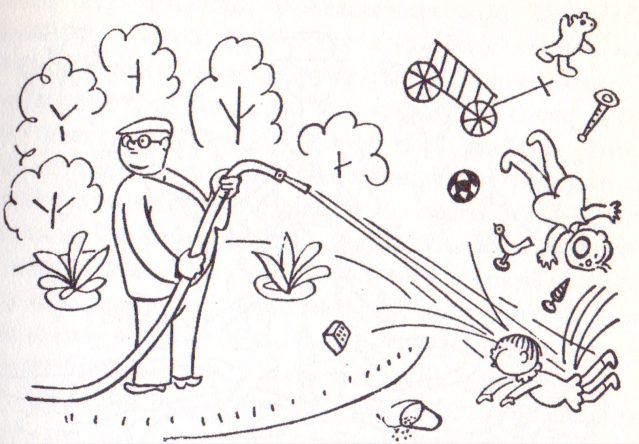

Pesticides also contribute to insect decline. These include insecticides and herbicides, both used widely in in commercial agriculture. Researchers recently concluded that one type of pesticide in particular, neonicotinoids, have been especially detrimental to monarchs.

Herbicides contribute to insect decline as well. Native plants survive in between furrows and on the edges of fields. When farmers spray between furrows to eradicate plants that compete with crops, they destroy the insects’ habitat.

Why does this matter? Like the Dust Bowl, insect decline is an unintended consequence of human actions—and like the Dust Bowl, it’s going to be a disaster. To start, birds eat insects. Some birds eat only insects. So if we want birds, we need insects—as do fish, turtles, frogs, bats, and all the other creatures for whom insects are food. We’re seeing reductions in numbers of all of these. More directly, we need insects to pollinate our food supply. “Without insect pollinators, flowering plants – and the foods they produce – would disappear,” says Jason Cryan, director of the Natural History Museum of Utah.

Bring back natives

The story doesn’t end here. There’s good news. People are recognizing this problem, and many home gardeners are taking steps to restore ecological function to our landscapes by planting native plants. We’re excited about work of Doug Tallamy, who has done so much to popularize these ideas with his bestselling books, like Nature’s Best Hope and Bringing Nature Home. (Incidentally, Tallamy will be the keynote speaker at the Northwest Missouri Master Gardener Conference in St. Joseph in September.) He has done a great deal to educate us about the role of host plants in supporting caterpillars through informative talks and initiatives like Homegrown National Park.

I never thought I’d be interested in insects, but there you go. It’s not just me. I was happy to see that my friend who asked about native plants added some butterfly milkweed to her annual bed this summer. That’s how I started, with just one plant. My family bought me a Asclepias incarnata, swamp milkweed, for Mother’s Day. I was surprised that it grew so tall! Now my yard contains over seventy types of native plants—and I’m not done yet!

There’s a lot to learn, though. The body of knowledge is significant and so is the learning curve, but it’s fascinating. I’ve gotten to know some great people through this shared interest, too, and I get a lot of satisfaction from helping instead of hurting.

I’m going to end this with a plug for a program I’ve been helping with this summer. Since I haven’t been blogging, I haven’t talked about it much, but the Deep Roots Habitat Garden Tours have been a wonderful opportunity to see native plants in action, a chance to visit several marvelous residential gardens. The tours take place on second Saturdays throughout the growing season, and the next one is this week. On July 13, 2024, we’ll be touring three prairie plantings around the I-435 loop.

I can’t wait, and hope to see you. Thanks for reading!

Resources

Presettlement Prairie of Missouri – 1981 book by MU geology professor Walter A. Schroeder. Portions available online: https://www.olivetteparksandrec.com/uploads/4/2/6/9/42697661/presettlement_prairie_of_missouri.pdf

Prairie: an Iconic American Landscape / Mid-Continent Public Library:

https://www.mymcpl.org/story-center/about/woodneath-landscape/prairie-iconic-american-landscape

New ‘Detective Work’ on Butterfly Declines Reveals a Prime Suspect / New York Times:

https://www.nytimes.com/2024/06/20/climate/butterfly-declines-insecticides-monarch.html

3 Billion Birds Gone / American Bird Conservancy:

A World Without Bugs / Natural History Museum of Utah:

Nature’s Best Hope – Conservation That Starts in Your Yard with Doug Tallamy / Cary Institute for Ecosystem Studies:

Gardening for Life – Doug Tallamy / Homegrown National Park:

https://homegrownnationalpark.org/not-in-our-yard-doug-tallamy

Habitat Garden Tours / Deep Roots: