My heart sank when I came home last week and saw Mosquito Joe signs—five of them—lining my street. I don’t blame anyone for disliking mosquitos, but I wonder if my neighbors know about the objections to these sprays. They don’t just kill mosquitos, they kill all insects, including butterflies and bees. And while we may not think of that as a problem, it is one.

Today I’m diving deep into the subject of mosquito sprays.

Many young families have moved into our neighborhood recently—we have four-year-olds on all sides—and we love hearing their voices as they play. Who wouldn’t want to protect kids from mosquitos? Mosquitos are a nuisance and carry diseases. Nobody likes mosquitos.

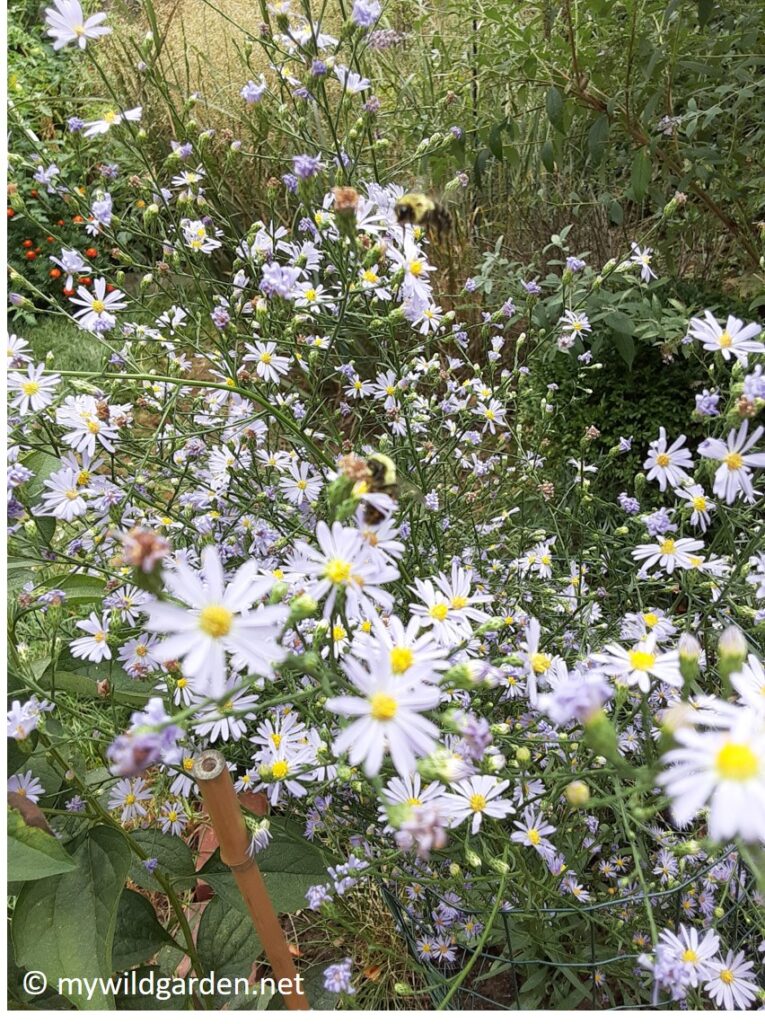

However, spraying for mosquitoes kills helpful insects too. These days, many people understand how important pollinators are, and that they’re disappearing. Loss of habitat, disease, loss of diversity, and pesticides are primarily to blame. This is a disaster in the making, because an estimated one-third of our food supply requires pollination.

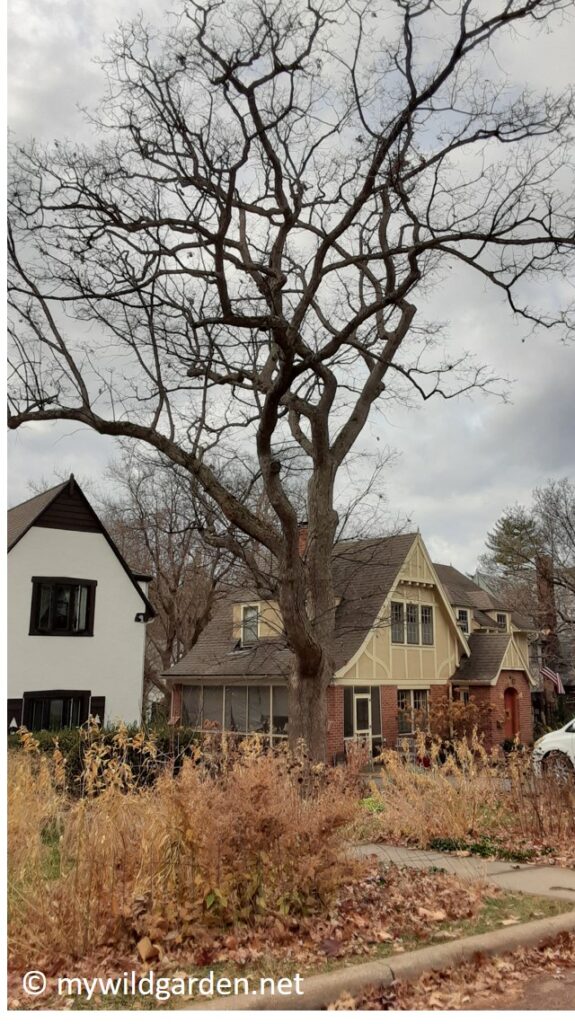

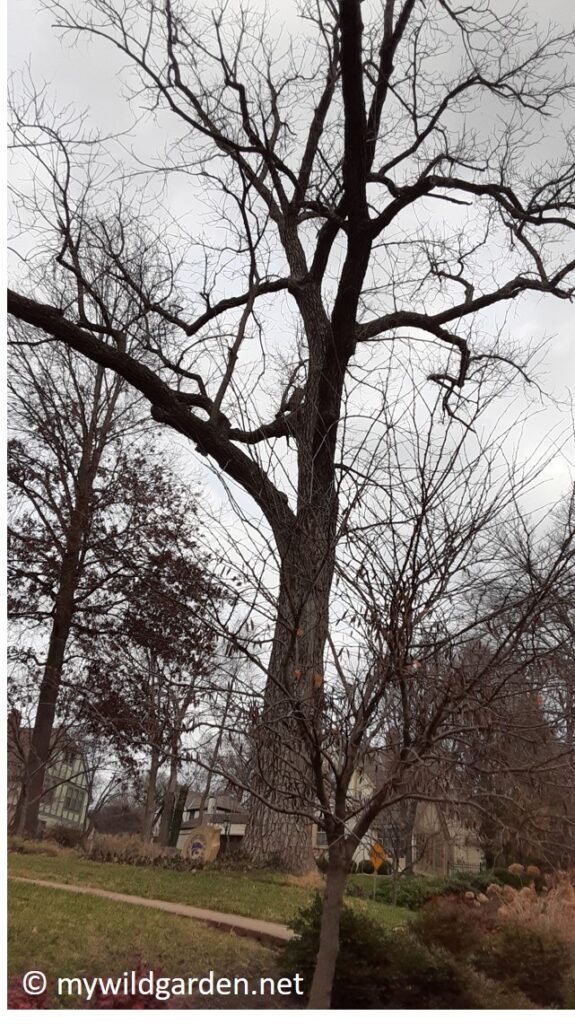

It’s happening in front of us. For years my family has enjoyed sitting outside in summer, watching the butterflies flit above our patch of native prairie plants. But for the last two years, we’ve barely seen any, I suspect because our neighbors spray.

I feel like I set a banquet and murdered the guests.

Spraying pesticides can have unintended consequences. Remember the food chain? Now the metaphor of a food web is more popular, but the idea is the same: each creature survives by feeding on other, “lesser,” creatures. Plants support insects, which feed birds and bats, and so on.

Most people have also heard that bird populations are declining, but we may not realize the connection to pesticides. Birds eat insects. Fewer insects means fewer birds.

The poisons in sprays like Mosquito Joe’s are pyrethrins, which some companies’ marketing materials claim are safe and organic. This is misleading. While it’s true, pyrethrins are a derived from an insecticide extracted from a type of chrysanthemum, it’s not like they’re sprinkling flowers on your yard. Pyrethrins kill insects instantly. That’s the point. They’re also toxic to fish, amphibians, and cats.

But all of this has been said elsewhere. What can we do? Getting rid of mosquitos is a good goal. Encouraging butterflies and bees is a good goal, too. Can we have both?

Ways to control mosquitos without poison

Remove water sources. Mosquitos lay eggs and hatch around standing water. Eggs take seven days to hatch, so once a week, empty any flower pots and saucers, buckets, etc. Make sure your rain barrel is tightly covered.

Turn on an oscillating fan. Mosquitos like stagnant air and dark, humid areas like underneath patio furniture. Blow them away with a nice breeze and enjoy the cooling effect.

Spray bug repellent containing DEET. I know, I don’t like it either, but it works.

Maybe you’ve tried these, but they didn’t do enough. Here are some ways to level up.

Repellent Devices

The New York Times’ Wirecutter recommends the Thermacell E55 Rechargeable Mosquito Repeller. It works by emitting an DEET-free, odorless repellent, and covers about 20 feet.

“Its rechargeable five-and-a-half-hour battery lasts long enough to odorlessly keep a bedroom-sized area mosquito-free for an entire evening—as long as there’s no breeze.” (I assume wind blows away the repellent.) The cost is about $40, plus the expense of additional cartridges.

A less-expensive alternative is Pic Mosquito Repelling Coils.

At $7, they’re as effective as the Thermacell E55, but because they’re burned, they emit an odor, which some people dislike. They may be worth a try, though.

Traps

These work by emitting C02, which attracts mosquitos and then traps them in a reservoir. A friend recommends Biogent’s BG-Mosquitaire CO2 .

He lives by a creek and had a serious mosquito problem but keeps bees, so spraying was out of the question. He says the trap was effective, and that he removed thousands of mosquitos from it each week. The downside is it’s expensive, $279 on the website, plus the cost of replacement CO2. And it requires some effort to maintain: the trap must be emptied. Other, less-expensive CO2 mosquito traps are available as well.

What doesn’t work

Bug Zappers. These are great at killing bugs, just not mosquitos, which aren’t attracted to light.

Citronella. If it seems like it works, it’s probably because of the smoke. Smoke works.

Repellent bracelets. These repel mosquitos from your wrist, but they may bite you someplace else.

Spartan Mosquito Eradicator. Some folks on Nextdoor recommended this product, and I’m sorry to disappoint them. This could definitely kill mosquitos—but not as an alternative to pesticides. The active ingredient is boric acid, a lethal insecticide. It claims to attract with sucrose, sodium chloride, and yeast, none of which do anything to attract mosquitos. This product has been accused of making false claims and has been banned in many states, including Kansas. (I verified this through a call to the Kansas State Attorney General’s Office.) This post by blogger Colin Purrington explains in more detail. It’s kind of fascinating. Apparently, people crediting it for the disappearance of mosquitos in their yards are mistaken. The real reason is that mosquitos were killed by insecticides sprayed nearby.

Talk about the passion

While researching this topic, I read about a man in San Antonio who is facing aggravated assault charges after allegedly beating his roommate over an argument about mosquitos. Clearly, this subject arouses strong feelings! It does for me, too. Seeing those signs in my neighborhood left me feeling distressed, and I hope you feel that way as well. If you or someone you know is considering spraying for mosquitos, please reconsider. Try one of these other methods first. Many of us are willing to do things to help the environment, but we need them to be easy, and we need them to work. These might be both!

References

https://www.ree.usda.gov/pollinators

https://www.nationalgeographic.org/encyclopedia/food-chain/

https://www.audubon.org/news/north-america-has-lost-more-1-4-birds-last-50-years-new-study-says

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2946087

https://colinpurrington.com/2021/08/spartan-mosquito-eradicator-updates/