Instead of posting regularly as I planned, I now seem to be posting when inspiration strikes—as it did last week when I read a discussion of this article from last Sunday’s Kansas City Star:

I’ve lived near this house for years and have followed this story with interest. On Facebook someone commented that they liked seeing the yard go “natural.” This got me thinking. Despite what one photo caption says, few would consider this landscape “native” or label this “naturalistic gardening.”

I’m all for bucking convention and rethinking lawns. But neglecting a yard does not fulfill conservation goals in any meaningful way. Instead of supporting necessary bugs and birds, not-mowing provides an opportunity for invasive species to move in—like dandelions, clover, and creeping Charlie (not to mention rats). These may be succeeded by brushy shrubs, especially Asian bush honeysuckle (Lonicera maackii, L. tatarica, L. morrowii, and L. x bella). In front of this house, Asian honeysuckle is growing in the gutter.

In fact, this shrub can grow almost anywhere, including shade. Its white or pink flowers are fragrant for a few days in May, and birds like its pretty red berries. (Everything I read says the berries have low nutritional content, like they’re Doritos for birds.) Asian honeysuckle is among first shrubs to green up in spring and last to lose leaves in fall. This makes it easy to spot in our landscapes, as in this photo.

In this case, easy-to-grow means easy-to-spread. According to the Missouri Botanical Gardens, Asian bush honeysuckle was first imported to the U.S. from Europe in 1897 through seed exchanges among botanical gardens. The USDA promoted its use from 1960-1984, although the plant began escaping from cultivation in the 1950’s. In Missouri, the first documented escape was in in 1983. Now it’s so widespread I can’t imagine walking in a forest without seeing it. It’s not just a problem in our area: it ranges from the east coast to the Midwest and has appeared in Oregon. The plants take over entire forests and crowd out other, native species, reducing habitat for wildlife—including butterflies—that depend on native plants to survive. It’s been linked to an increase in ticks and is apparently a preferred egg-laying host for mosquitoes. It can be challenging to eradicate.

American forests have been irrevocably changed by this plant. It is insidious. This is what will be growing in our yards if we stop taking care of them.

Sometimes you must name a thing to see it. This morning I passed beneath a red tail hawk flying in relaxed, seemingly aimless circles over the road—making lazy circles in the sky. I might not have understood that the banks of Brush Creek had become a monotonous monoculture before I learned to spot Asian honeysuckle. It’s as ubiquitous as trash.

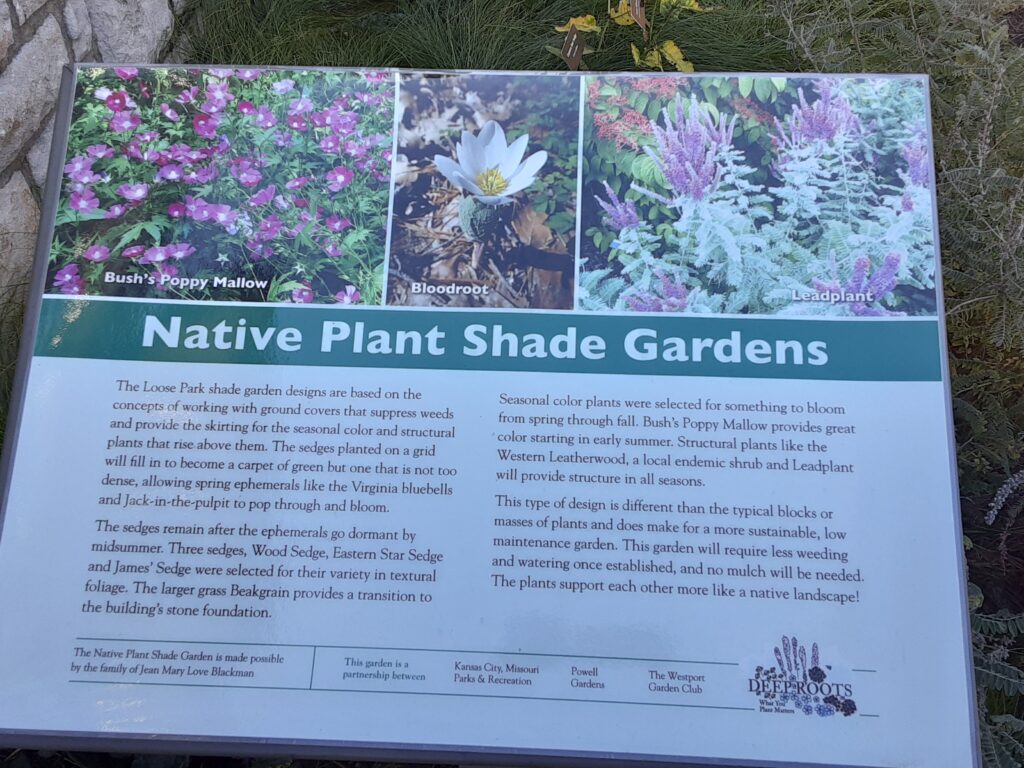

Being more mindful about what we plant can yield amazing results. The “rat house” is next door to fabulous example of what a natural or native garden can be. Dana Posten’s pollinator garden is full of rich, diverse plantings, with very little turf grass. Its beauty delights many passers-by. It’s a planned environment, meticulously maintained—because everything we care about must be cared for.

But preserving biodiversity doesn’t have to be a huge production. We don’t have to eliminate our lawns entirely, either. As people like Doug Tallamy and Rick Darke point out, even simple steps and slight adjustments can help us rewild our yards. Here is a list of Tallamy’s recommendations (from the Smithsonian Magazine‘s “Meet the Ecologist Who Wants You to Unleash the Wild on Your Backyard,” by Jerry Adler).

8 Steps to Rewild America

To Tallamy, the nation’s backyards are more than ripe for a makeover. Here are some of his suggestions to help rejuvenators hit the ground running.

1. Shrink your lawn. Tallamy recommends halving the area devoted to lawns in the continental United States—reducing water, pesticide and fertilizer use. Replace grass with plants that sustain more animal life, he says: “Every little bit of habitat helps.”

2. Remove invasive plants. Introduced plants sustain less animal diversity than natives do. Worse, some exotics crowd out indigenous flora. Notable offenders: Japanese honeysuckle, Oriental bittersweet, multiflora rose and kudzu.

3. Create no-mow zones. Native caterpillars drop from a tree’s canopy to the ground to complete their life cycle. Put mulch or a native ground cover such as Virginia creeper (not English ivy) around the base of a tree to accommodate the insects. Birds will benefit, as well as moths and butterflies.

4. Equip outdoor lights with motion sensors. White lights blazing all night can disturb animal behavior. LED devices use less energy, and yellow light attracts fewer flying insects.

5. Plant keystone species. Among native plants, some contribute more to the food web than others. Native oak, cherry, cottonwood, willow and birch are several of the best tree choices.

6. Welcome pollinators. Goldenrod, native willows, asters, sunflowers, evening primrose and violets are among the plants that support beleaguered native bees.

7. Fight mosquitoes with bacteria. Inexpensive packets containing Bacillus thuringiensis can be placed in drains and other wet sites where mosquitoes hatch. Unlike pesticide sprays, the bacteria inhibit mosquitoes but not other insects.

8. Avoid harsh chemicals. Dig up or torch weeds on hardscaping, or douse with vinegar. Discourage crabgrass by mowing lawn 3 inches high.