What I love best about June is nectarines and getting out on a lake, although here in the garden it’s a busy time. We’ve entered the pruning-watering-weeding time of year, with fabulous, abundant life existing alongside heartbreak and disappointment.

Someone on Facebook posted yesterday that he’d seen his first Japanese beetle of the year, and today I found mine. (I drowned it.) More are on the way. They turn up around the first week of July and devour, if not everything, then a lot of things. They’re kind of biblical. In our garden they prey on roses, hibiscus, and a grapevine.

That’s a grape growing along the back fence. We planted it around the same time the beetles first arrived in the area, 2014 according to the Star, so they’ve grown up alongside each other. Grapes grow well here. After eating dinner at a friend’s table beneath a pergola with bunches of grapes dripping down, we were entranced. Around that time, I was going through old issues of Gourmet, reading the articles I’d skipped originally while looking for chicken recipes, and discovered this exhaustive Wine Journal piece by Gerald Asher from April 1993.

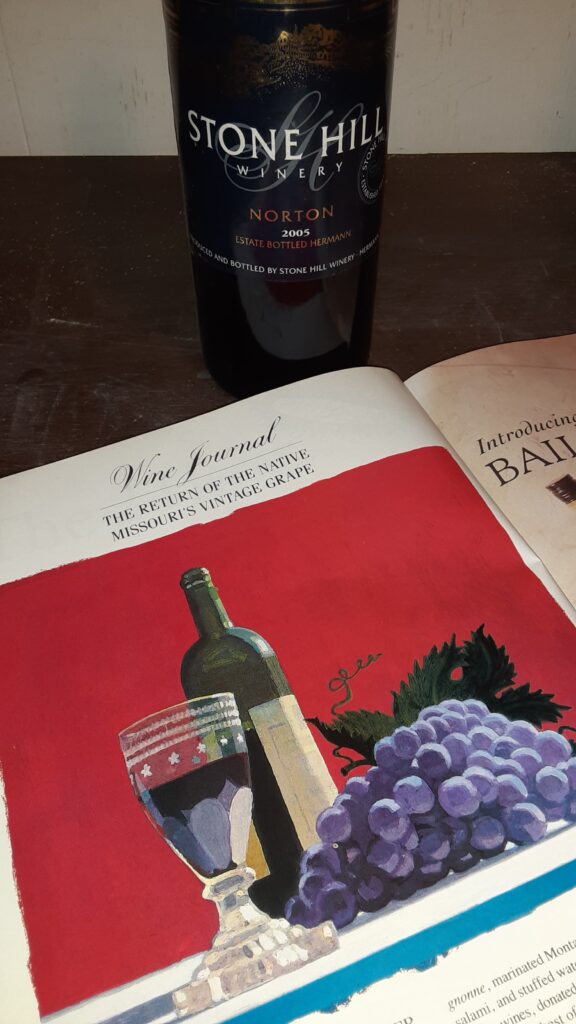

This article, called “The Return of the Native: Missouri’s Vintage Grape,” deserves more comment. Asher visits Hermann, Missouri’s Stone Hill Winery and enthuses about the Nortons, saying, “I was astonished to find the wines so remarkably good. They were more meaty than fruity, with something of the Rhone about them.” Asher then recounts the history of viticulture in the Midwest, beginning in the early 1800s in Ohio, followed by the establishment of Hermann’s vineyards in the 1830s by German settlers fleeing “revolutionary disturbances.” A first, two kinds of grapes, Catawba and Norton, vied for predominance. Catawba was used to produce a sparkling wine, while Nortons are rich reds: “an indigenous American grape that might yet do for Missouri what Cabernet Sauvignon has done for California.” Winemakers produced sparkling wines from Catawba quickly, while Norton requires aging for four to five years—“as do most potentially great red wines”—so early growers emphasized Catawba to maximize profits. However, Catawba is vulnerable to mildew and rot, common conditions in our humid summers, while Norton is tougher, better suited to our weather extremes. Ultimately, Norton won out, and in the 1870s, wines produced in Hermann were winning gold medals in international competitions.

Missouri’s wine industry never fulfilled its early promise. Labor costs and the temperance movement chipped away until the passing of the 18th Amendment finally killed it. Plus ça change. Asher describes links between Prohibition and racial prejudice, showing how the movement exploited anti-German sentiment. Reborn in 1965, Missouri vineyards have continued to grow, although slowly. While it may not have the cachet of a tour of Napa, visiting Hermann is definitely a thing, as the drunks I sat with on the Amtrak during Oktoberfest can attest. Asher says this:

Tens of thousands of visitors come to the town every year, and, although they arrive expecting little more than a jolly picnic, a hop to a polka band, and a few bottles to take home, most leave with a greater appreciation of the state of Missouri; possibly with a broader feel for its history; and, especially at the time of the fall grape harvest festivals, with indelible memories of the Missouri River valley’s beauty.

(Read more about Missouri grape varietals on the Missouri Wine website. If you’d like to read Asher’s entire article, let me know in the comments and I’ll send you a pdf.)

So, what does all this have to do with gardening? Energized by this new knowledge, we bought this Vitis labrusca ‘Reliance’ at Soil Service. (These are table grapes, for eating, not for winemaking.) My husband built a trellis along the south end of our yard, we planted the grape, then sat back and waited for our vine to bear fruit.

The south end of the yard does not get as much sun as I’d anticipated, and the grape struggled. The west side is shaded by the neighbor’s oak leaf hydrangea, so it’s kind of spindly there. The east side is sunnier, so it grew in that direction. I don’t know why, but this year it found its moxie and has sprawled beyond the trellis onto the fence.

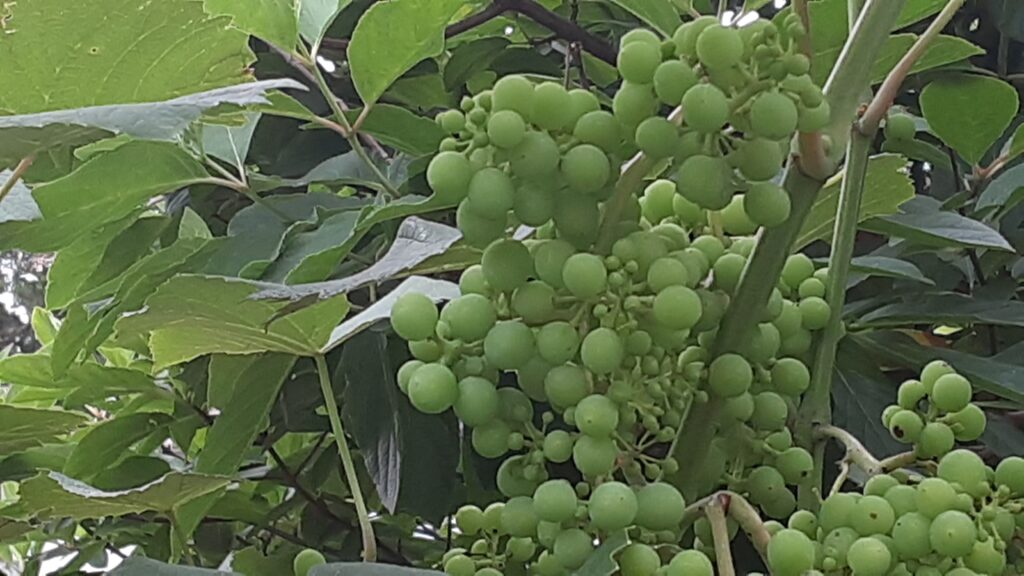

The vine is bare for much of the year, which isn’t great to look at, but it leafs out nicely every spring and big clusters of green grapes begin to form. The birds and I watch them carefully as they ripen. Then, all of a sudden, they vanish. In all these years, have never eaten a grape grown on this vine.

This is happening now. The back fence has been twitching with birds lately, finches and cardinals. I thought the feeders had attracted them, but went out to take a look and found the great green bunches growing.

For the last two or three summers I’ve tented them with black tulle. Tulle is the net fabric used to make ballet tutus, and I bought a bolt for about twenty dollars. The holes are too small for the beetles to pass through, and birds can’t penetrate them, either. I tossed the fabric over the blueberries this week to protect them from the birds, so you can see what it looks like.

It’s not the toughest fabric and has deteriorated in the sun, so it’s shrinking in size as I cut off damaged sections. The blueberry looks like a ghost. Nevertheless, the tulle is pretty effective against beetles and birds, and if those were the only pests, I’d recommend it.

But those aren’t our only pests.

HELP!

While birds and beetles bombard from above, chipmunks climb up and chow down on those grapes. A quick internet search turns up many suggestions for controlling chipmunks, so I suspect none work. We ran into this recently with Carpenter bees, which were tunneling into our porch roof. I was going to write a post saying I’d found the perfect pesticide-free remedy, but nothing deterred them. Squirting citrus oil just agitated them. Plugging the holes with steel wool meant cleaning clumps of steel wool off the porch every morning. I think if something really works, there will be a consensus. Everyone will mention it. That’s not the case with chipmunk strategies.

Besides, the grapes have another, more insidious problem. Black Rot is a fungal disease that mummifies the fruit, shriveling it and turning it black. Probably this is the “mildew and rot” Asher blames for destroying the early grape industry in Ohio. Apparently it is controllable with appropriate pruning and properly applied fungicide, neither of which I have done.

Let It Be

This morning I snipped off the clusters that had black spots, and tied paper bags around the ones that didn’t. I know, this will not work. I’ve tried the paper bag method before. The birds (or squirrels) just slash them open. The best thing to do, at this point, is nothing. I’m going to sit on my hands and watch the critters eat, enjoy the things that aren’t having problems, read up about pruning, and dream about next year.

References

“Japanese beetles have finally arrived in KC.” Kansas City Star. June 17, 2022. https://www.kansascity.com/living/liv-columns-blogs/kc-gardens/article693046.html

Gerald Asher. “Wine Journal: The Return of the Native Missouri’s Vintage Grape.” Gourmet. April 1993. 42-48, 252-253.

Oktoberfest. https://visithermann.com/events/festivals-in-hermann-missouri/?utm_source=Madden&utm_medium=GoogleCPC&utm_campaign=Festivals&gclid=Cj0KCQjwzLCVBhD3ARIsAPKYTcQN_nw7oOL_huAF9b2mX-3xWK7BGUH1wx-UW8Rl4vB4Lek5RPiKfu0aAp5yEALw_wcB

Ellis, Michael A. Controlling Grape Black Rot in Home Fruit Plantings. Department of Plant Pathology The Ohio State University/OARDC. https://ohiograpeweb.cfaes.ohio-state.edu/sites/grapeweb/files/imce/Controlling%20Grape%20Black%20Rot%20in%20Home%20Fruit%20Plantings.pdf