Why then presume to write a book about gardening? The simplest answer is that a writer who gardens is sooner or later going to write a book about the subject—I take that as inevitable. One acquires one’s opinions and prejudices, picks up a trick or two, learns to question supposedly expert judgments, reads, saves clippings, and is eventually overtaken by the desire to pass it all on.

from Green Thoughts: A Writer in the Garden

Almost every list of classic gardening books includes Eleanor Perényi’s Green Thoughts: A Writer in the Garden. The third of the reissued Modern Library Gardening series I read last fall (in addition to The Gardener’s Year and We Made a Garden), it was my favorite. Originally published in 1981, Green Thoughts consists of 72 alphabetically arranged essays about random topics close to the author’s heart. She lavishes praise on compost, dahlias, perennials, and toads, and condemns annuals and pesticides. Labeled “tart” and “opinionated,” Perényi is definitely all that, as well as erudite (her references include Theophrastus and Pliny) and culturally sophisticated. Her entry about J.I. Rodale is so exhaustive, I thought she must have researched him for a magazine profile—which she did, “Apostle of the Compost Heap,” which appeared in the July 30, 1966 edition of The Saturday Evening Post.

Who was this person? Eleanor Perényi was accomplished enough to merit a New York Times obituary when she died in 2006—she lived to be 91, despite being an unrepentant smoker. She earned an award from the Academy of Arts and Letters in 1982, and counted poets J.D. McClatchy and James Merril among her friends. In addition to a decades-long career writing and working at magazines, she published four books: The Bright Sword (1955), a romance set during the Civil War; a biography, Listz: The Artist As Romantic Hero (1974); Green Thoughts; and a memoir, More Was Lost (1946). She may be best remembered for Green Thoughts, which I enjoyed enough to seek out her other titles. However, for me, More Was Lost is her masterpiece.

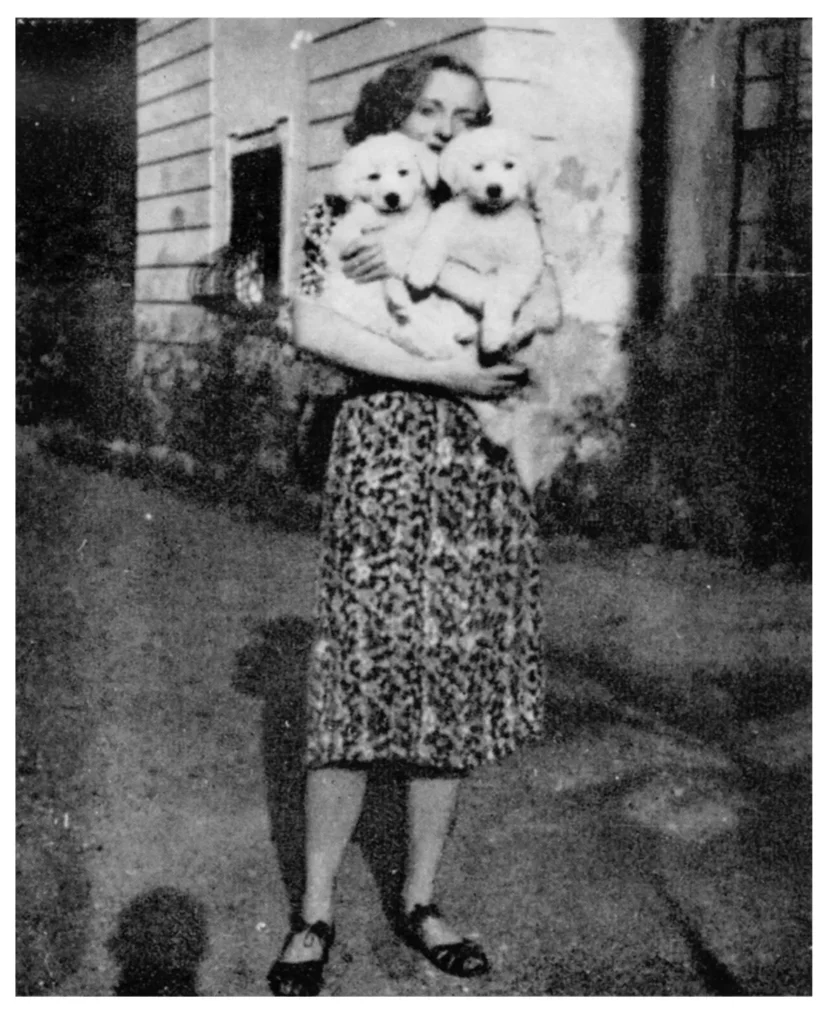

It tells about her marriage to a Hungarian count during the days leading up to World War II. In 1937, then-Eleanor Spencer Stone marries Baron Zsigmond (Zsiga) Perényi, an impoverished Hungarian aristocrat. He was 37. She was 19. They move together to his derelict estate, “on the edge of the Carpathians,” in Ruthenia. I had to Google Ruthenia to visualize where it is. Its drama is written on the map. The estate straddles the borders of Ukraine, Slovakia, and Hungary. Some place names are written in the Roman alphabet. Others are in Cyrillic. You know what’s coming, and it isn’t good.

More Was Lost leaves deep impressions. It offers a fascinating glimpse of little-known part of world and lost civilization through the eyes of an astute observer. After the couple arrives at their estate, Eleanor describes the touring the castle rooms, delighting in the books and furniture.

There were the books and the maps; and this room, too, was frescoed. On the vaulted ceiling there were four panels, representing the seasons of the year. In the firelight, with the red brocade curtains drawn, this room seemed to vibrate with faint motion. Everything moved and looked alive, the gleaming backs of the books, the shadowy little figures on the ceiling, and the old Turk over the fireplace.

She claims she never wanted to create a home from scratch but preferred to move into an already furnished one, as if it were waiting for her.

My favorite idea as a child was what happened in French fairy stories. You were lost in a forest, and suddenly you came on a castle, which in some way had been left for you to wander in. Sometimes, of course, there were sleeping princes, but in one special one there were cats dressed like Louis XIV, who waited on you. Sometimes it was empty, but it always belonged to you without any effort on your part. Maybe it’s incorrigible laziness, but I like things to be ready-made. And when I went into my new home, I had just the feeling of the child’s story. It was all there waiting for me. This house was the result of the imaginations of other people. If a chair stood in a certain corner it was because of reasons in the life of someone who had liked it that way. I would change it, of course, but what I added would only be part of a long continuity, and so it would have both a particular and a general value. If we had built it, it would certainly have been more comfortable, and perhaps even more beautiful, but I doubt it, and I should have missed this pleasure of stepping into a complete world. And there would have been no thrill of discovery. As it was, I ran from room to room, examining everything. I liked it all.

I find it unusual for nineteen-year-old to hold such thoughts. The ones I know are determined to reject tradition as limiting.

Reviving the production parts of the estate, the fields, forest, and vineyards, would be Zsiga’s responsibility. The grounds, the ten-acre garden, and the orchard, would be hers. There is gardening in More Was Lost, as she describes getting to know the local traditions and tradespeople.

A flagged path led from the gardener’s house down to the vegetable garden. A white fence along the length of it shut off the chicken houses and the pigsty. I liked the chicken houses because of the Hungarian names for poultry, “little beef,” or better still, “the winged.”

There was a pretty white cottage in the vegetable garden, covered with grapevines, where the gardener kept his tools, little packages of seeds, and the oddments that collect around a gardener. There was also a greenhouse… There were oleander, papaya, and datura trees in big tubs and cactus and pals. There were hundreds of pots of little laurel bushes, fuschia plats, chrysanthemums, and begonias, and I found that all this in the spring would be stacked on wooden stands around the house—except for the trees, which were arranged artistically on the lawn.

She faces all challenges with aplomb. The idyll proves short-lived, however. Perényi is out planting tulip bulbs with her sheepdogs in 1939, when she hears distant gunfire. The war has arrived. Czechoslovakia was no more.

You know the rest. There is no one moment when everything changes. Instead, they listen to the radio and make daily adjustments as the area passes from Czech to Ukrainian to Hungarian control. She describes management styles of each. For instance, she says the Hungarians had no managers. They were aristocrats who disdained work, or peasants unaccustomed to making decisions. The manager types, the bourgeoisie, were nonexistent. When the Hungarians took over, it was chaos.

Before that, in the summer of 1940, she travels to Paris, where her parents were living, and is there when the Maginot line collapses and the Nazi occupation begins. She goes back to the estate, but leaves again later that year at Zsiga’s urging—“as if I expected to be back the following week.” She never returns.

Eventually Perényi settled in Stonington, Connecticut, where she gardened on a 10-acre property purchased by her mother, Grace Zaring Stone, who was popular writer in the thirties and forties. Stone’s novel The Bitter Tea of General Yen was made into a film starring Barbara Stanwyck. She was also known for an anti-Nazi thriller, Escape, published in 1939 under the pseudonym Ethel Vance to protect Eleanor, who was living in occupied lands. The two lived together until Stone’s death in 1991. As of 2022, the property continues to be occupied Perényi’s son Peter, although he is in his eighties now.

Eleanor Perényi may not be well known today, but many of her most ardent fans appear to be bloggers. I gleaned almost all this information from blog posts, piecing scraps together to make a story. I must have read at least fifty posts. Most target gardeners by focusing on Green Thoughts. Posts about More Was Lost are usually on book blogs, and aim to resurrect interest in this neglected writer—although they could be considered gardening adjacent, like this post.

Some of the appreciations are very good, like this on a blog titled Eiger, Monch & Jungfrau. More Was Lost was reissued by New York Review Books in 2016. An excerpt appeared on LitHub in February of that year.

Much of Perényi’s magazine work is available on the internet or through college libraries. To be honest, her “tart” and “opinionated” work is sometimes strident and prejudiced (although one writer says, “she was deeply sympathetic to the growing civil rights struggle, and chose not to list the novel [The Bright Sword]—with a southern general as its hero—on her subsequent book jackets”).

If someone were to establish an Eleanor Perényi fan club, I would join. This versatile writer would make a fascinating topic for a critical biography, dissertation, or something. (Her mother would, too.) Perényi’s papers are archived at Yale.

Now that it’s warming up outside and the sun is shining, I’m eager to get out and do some actual gardening of my own instead of just reading about it. My ambition this spring is a massive redo of my backyard beds, but using the plants I already have, just moving them around—tall in back, shorter in front, no singletons, that sort of thing. It sounds like a lot of digging. We’ll see how I do.

I’ll keep you posted. Thanks for reading.

References

https://www.penguinrandomhouse.com/books/129540/green-thoughts-by-eleanor-perenyi/

“Eleanor Perenyi, Writer and Gardener, Dies at 91.” May 6, 2009. https://www.nytimes.com/2009/05/07/books/07perenyihtml?ref=obituaries

“Our Story.” Rodale Institute. https://rodaleinstitute.org/about/our-story/

The Bitter Tea of General Yen. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Bitter_Tea_of_General_Yen

Escape. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Escape_(1940_film)

Eiger, Monch & Jungfrau https://eigermonchjungfrau.blog/2016/06/04/a-long-continuity-eleanor-Perényis-more-was-lost/

More Was Lost excerpt, LitHub, https://lithub.com/more-was-lost/

Stonington Revisited: Eleanor Perényi and Grace Zaring Stone by Richard Teleky. https://muse.jhu.edu/article/579777

Eleanor Perényi papers, Archives at Yale. https://archives.yale.edu/repositories/11/resources/11858